Seeing Documentary as Dialogic Art. (Summary of work in progress)

This research with the Department of Film and Screen Media at University College Cork is funded by the Irish Research Council Postgraduate Scholarship scheme. https://research.ie/funding/goipg/

This research takes as a starting point the illusion of completely ethical participation of subjects in documentary film. Experiments in the participation of human subjects in the production of a documentary film promised to address some issues relating to authorial projection and editorial control. This page is a journal/ scrapbook of various methods that have been used in film and contemporary art to attempt to address these issues. What follows is a short summary of this research.

Abstract

Anthropologist and filmmaker Jean Rouch experimented with active subject participation in the production of his films. Les Maîtres Fous (1955), depicted a group of Haika people in Niger engaging in spirit possession rituals, and acknowledged that the participants in the film were performing for the camera. Rouch’s ‘ethnofictions’ understood that due to the many variables at play, film could never be an objective representation of reality. Instead he embraced the most prominent of these variables – the subjects as active participants in his productions. If it is impossible to faithfully represent a group of people from an authorial point of view, the most ethically responsible thing to do is to allow them agency in the production of their own image. These experiments were not without flaws, and later, more elaborate experiments, such as Chronique d'un été (1961) showed that representation of participants can be heavily guided by editing techniques. A separate art-form that has taken up the challenge of ethical representation is participatory art. Also known as ‘dialogic art’ it emphasises productive collaboration with groups of participants as a core method. Central to the ideal of participatory art is the element of the unpredictable – removing the potential for absolute control away from the artist and opening up a space for discourse. This art-form challenges the notion of power in representation, and the notion of art itself as privileged or as commodity. This conference paper will examine instances where documentary film and participatory art methods have overlapped, and will propose that the two art-forms have various common objectives. It will look at the work of Turner Prize winning artist Jeremy Deller, from his 2001 re-creation of a miner’s strike battle with police which was documented by filmmaker Mike Figgis, to his 2019 film Everybody is in the Place: a filmed lecture about UK rave-culture in the 1990’s, mediated through the participation of a group of secondary school students. It will also look at films that more closely identify as ‘documentary’, but with strong elements of participant influence, such as Island (2017) by Steven Eastwood, about residents in a hospice who consented to having the ends of their lives documented on film. Finally it will ask if an identification of this intersection of disciplines can create a new space for the consideration of all documentary films involving human subjects as works of participatory art.

Cinéma Vérité

This early experiment in participatory documentary was flawed, but set a precedent for other such experiments, and laid the groundwork for a genre of observational documentary filmmaking.

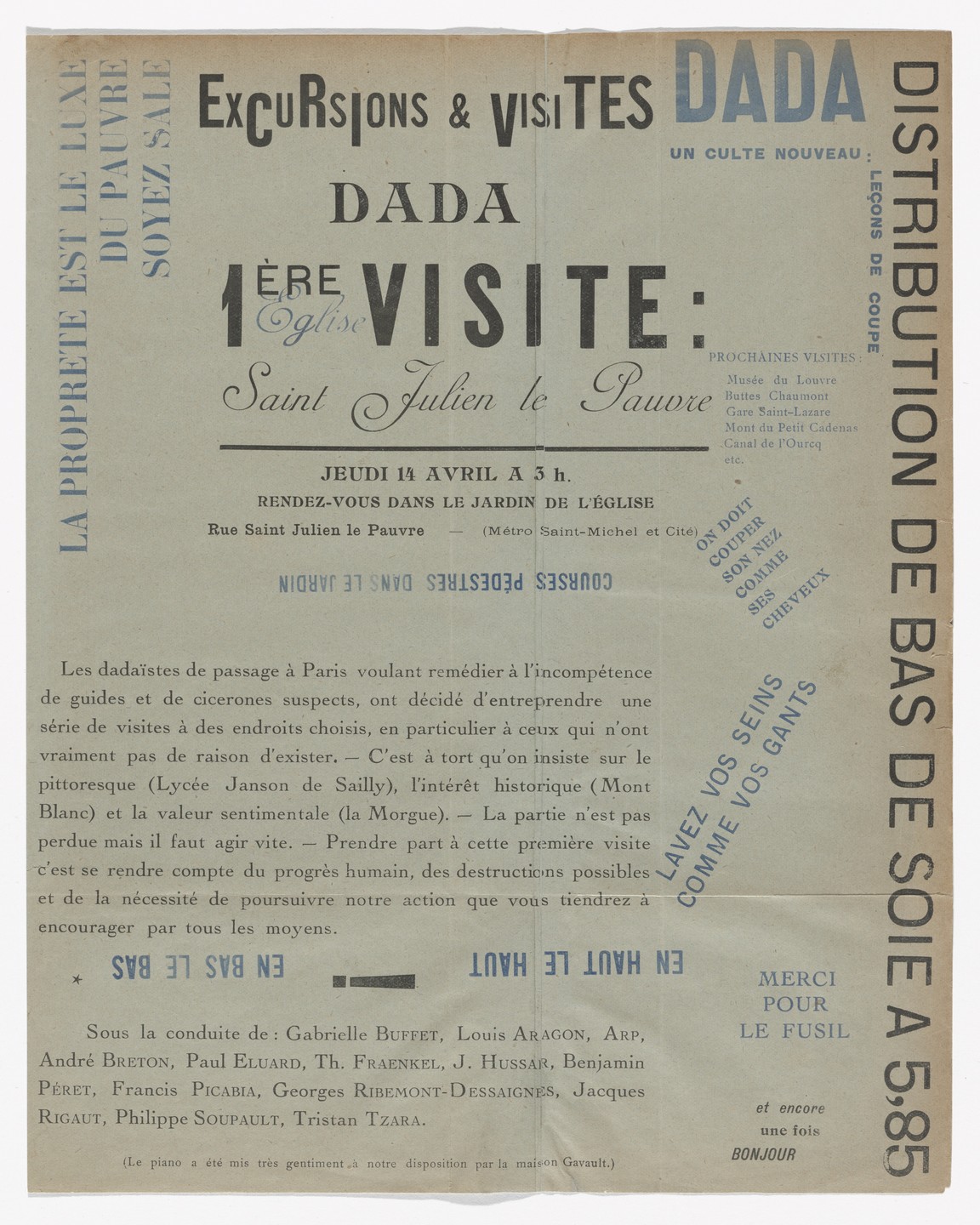

Excursions et Visites. Jeudi 14 Avril, 1921.

One of the first known experiments with (what is now called) participatory art took place in 1921 in Paris, organised by Dada artists André Breton, Tristan Tzara and others. The event was titled: Excursions et Visites and was a type of absurd and nonsensical guided tour of Paris, beginning at the churchyard of Saint Julien le Pauvre. It was a failure, it rained, and nobody turned up (many of us artists can relate to this). The intention, however was to create a public artwork, where the 'audience' became more than spectators, but active participants in the work.

An earlier (and perhaps the first) ethnofiction was Les Maîtres Fous (1955). Styled more like a conventional ethnography, this film shows rituals of the Hauka movement in Niger, who are shown as being possessed by the spirits of former colonial masters. The beauty of this film for me is summed up by this reaction to it by Amy from The Movie Checklist youtube channel, who is horrified that she really cannot find a genre to attach to it (she does mention 'mocumentary' at one point...).